Meet the hacker mom big companies hire for cybersecurity

(originally published on NBCNews.com)

MISSOULA, Montana — Americans are under attack, and the weapon is now your computer. Every 40 seconds, there is a cyber attack. The criminals are getting smarter, and their attacks are getting more and more sophisticated.

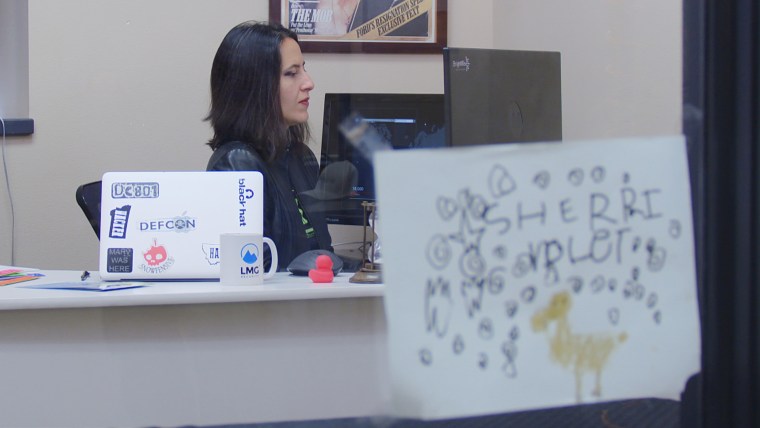

Our best line of defense may not be the FBI or Congress, it may be people like 38-year-old Sherri Davidoff. Davidoff, a mother of two who lives in this scenic college town at the foot of the Bitterroot Mountains, is a “white hat” hacker — meaning she hacks into computer systems, but for the good guys.

“We’ve seen this whole hacker economy evolve. And that means it’s no longer 13-year-olds in their mom’s basement that are hacking us,” said Davidoff. “It is organized crime groups all over the world.”

The data backs that up: According to the 2018 Verizon Data Breach Investigative Report, 50 percent of all breaches were carried out by organized criminal groups.

Davidoff, an MIT grad, was one of the first female white-hat hackers in an industry still dominated by men. From an office in downtown Missoula that looks out on snow-capped peaks, she and an all-female management team run a national consulting firm called LMG Security, which is hired by companies to test their security.

LMG Security tests companies for their cybersecurity flaws. Often that means sending out emails to employees and calling, in hopes of getting them to click on a malware link.

LMG then assists them in damage control after they’ve been hacked and helps them get cleaned up so they aren’t repeat victims. They also hold security seminars for employees and executives, and help companies comply with cybersecurity laws and standards.

Anatomy of a hack

LMG’s war room is equipped with the same tools the bad guys, the “black hats,” use. It has rows of computer screens, malware purchased on the dark web, and spoofing tools that disguise everything from phone numbers to voices. Davidoff gave NBC News an exclusive look as LMG’s white hats prepared to hack an unnamed company to test for vulnerabilities.

“Attackers can send out 100,000 ‘phishing’ emails,” explained Davidoff, “and if one percent of people click on the link, that’s 1000 people they’ve infected.”

The team disguised their phone numbers and email addresses to look as if they were coming from inside the company, a tactic cyber criminals often use. Team members then sent out phishing emails with an address that looked like the messages were coming from the company’s own IT department.

The fake emails, offering the chance to ‘opt out’ of a four hour training, were meant to trick employees into clicking on a link that supposedly led to an online training site — but really just opened the door for hackers to get in.

If the employees took the bait and logged in, their passwords were captured. The “victims” then received an “error” message saying someone would be calling shortly. That’s when Davidoff’s team went to work with part two of the hack — the phone calls.

With numbers masked to look like they are coming from inside the company, Davidoff’s staff called the targets, claiming to be tech support to help with the error. The callers — who sounded frighteningly realistic — instructed the victims to download a form that would allow the virus to infect their computer systems. Some were suspicious and declined, but a few went ahead and clicked. It took mere minutes for Davidoff’s crew to find a few takers, and have an open lane to infecting the entire company’s system with a computer worm that could be absolutely devastating.

The white-hat team then repeated the process twice more for two other companies, with similar results.

Real life hacking situations look very similar to what Davidoff has set up — offices and all. Cyber criminals have gotten so good, she says, that cybercrime has turned into an entire underground industry, and criminals are increasingly employed by larger operations in a 9-to-5 job, only their job is to steal your information.

“In some cases, they’re businesses,” said Davidoff. “They are employing people that have families, and they don’t see it as breaking into your organization. They see it as work. The same way you go to work, they go to work.”

In fact, cybercrime has become so businesslike that if you were to buy one of these malicious programs on the anonymous part of the internet known as the “dark web,” they come with a manual — and tech support. One dark web seller advertised “full support” and a refund if you weren’t satisfied with your purchase.

The “dark web” is where cyber criminals go to purchase banking Trojans or other viruses that infect computer systems and can steal passwords, banking information, or documents that criminals can then hold for ransom.

These viruses are striking everywhere from small businesses to entire towns — and costing a lot of money in the process. The city of Allentown, Pennsylvania has its computer systems hacked in early 2018, compromising employee credential data and knocking out critical computer systems. The bill to clean up the mess left behind by the hackers and to ensure that it didn’t happen again? Nearly 1 million dollars.

How consumers can combat the hacks

The number one thing you can do to protect yourself from cybercrime, according to Davidoff, is “think before you click.” She advises against clicking on any emails that don’t seem familiar.

Number two is to back-up your data, so that if you do get hacked you won’t lose all of the important files you have in your system. Number three is enable two-factor authentication on things like your email accounts and mobile banking apps. That means using a second credential in addition to your password, like a code generated by an app on your smartphone. Davidoff says it’s a simple thing that everyone who uses the internet should do.

With the threats only increasing every year, Davidoff has been busy. She runs a second company from the same Missoula office called Brightwise, which specializes in cybersecurity training.

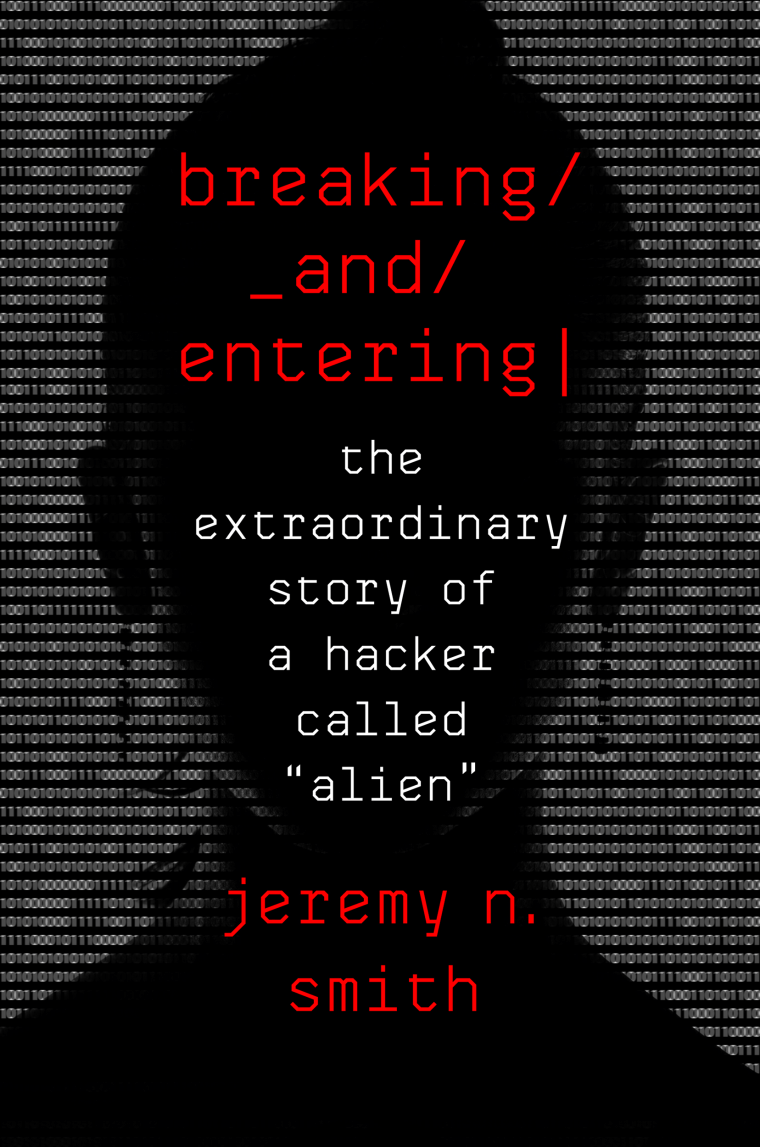

Her life, from the halls of MIT to running her own company and having children in the mountains in Montana, is now the subject of a book out this month called “Breaking and Entering: The Extraordinary Story of a Hacker called Alien.”

She does not see herself slowing down anytime soon and keeps a constant eye on the threats of the future. “The watches you wear, any coffee pots or refrigerators that are smart that you plug in, all of these are computers,” she said. This means that all of those are, potentially, hackable.

Davidoff says that we are entering a time period where homes can get infected with malicious software, and cybercriminals will eventually hold our own appliances for ransom.

“That’s where we’re headed in the next decade,” Davidoff said. “Sleep tight.”

Study shows Americans are forgetting about the Holocaust

(originally published on NBCNews.com)

By Courtney McGee

In 1945, Sonia Klein walked out of Auschwitz. Every day of the 73 years since she has been haunted by the memory of what happened there, and the fate of the millions who never made it out of the Nazi death camps.

But Klein wonders, once she and the few survivors still alive are gone, who will be left to remember?

“We are not here forever,” said Klein, now 92. “Most of us are up in years, and if we’re not going to tell what happened, who will?”

Klein’s worries are borne out by a comprehensive study of Holocaust awareness released Thursday, Holocaust Remembrance Day, which suggests that Americans are doing just the opposite.

Schoen Consulting, commissioned by The Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, conducted more than 1,350 interviews and found that 11 percent of U.S. adults and more than one-fifth of millennials either haven’t heard of, or are not sure if they have heard of, the Holocaust.

Of those who have heard of the Holocaust, many are fuzzy about the facts of a systematic campaign of murder that killed 12 million people, 6 million of them Jews. One-third of respondents — the number rises to 41 percent for millennials — think that two million or fewer people died.

“It’s a must for people to remember,” Klein said. The millions killed live through the survivors, she said, and “once we are gone they must not be forgotten.”

With the youngest survivors now in their mid-70s, the chance of hearing first-hand stories is rapidly dwindling. Two-thirds of Americans do not personally know or know of a Holocaust survivor.

American citizens are not alone: Entire countries are changing the way they remember the Holocaust, known in Hebrew as the Shoah. The Polish government recently passed a bill making it illegal to blame Poland for any crimes committed during the Holocaust. More than half of the people exterminated by the Nazis were from Poland. Auschwitz, perhaps the best-known concentration camp and the death site of almost 1 million Jews, is in southern Poland, where it has been preserved as a memorial.

Schneider said there has also been an increase in anti-Semitism, and Americans agree, according to the survey. Sixty-eight percent of respondents believe there is anti-Semitism in the U.S. today. Separately, data released by the Anti-Defamation League shows a 57 percent spike in anti-Semitic incidents in the U.S. in the past year.

The way to fix this growing problem, Schneider said, is education. Only nine states mandate Holocaust curriculum in schools, and each state offers varying degrees of detail.

While one third of the annual 1.7 million visitors to the Holocaust Museum each year in Washington are American students, 80 percent of Americans say they have never visited a Holocaust museum.

“Unless you know what happened,” Klein said, “you don’t understand what never again means.”

Get new content delivered directly to your inbox.